This is Graham Dineley writing this blog. All ideas, opinions and mistakes are entirely my own and my responsibility. I welcome comments and discussion, please feel free to do so.

It's a long time since 'beakers were for beer' parts 1, 2 and 3 were written by Merryn. Something happened recently that caught our attention and so the brewer decided to write part 4. It involves a television series, the Achavanich Beaker and there's some Grooved Ware thrown in at the end for good measure.

BBC's "A History of Ancient Britain" with Neil Oliver

Early last year, April I think, we were making silk face masks during lock-down to give to family and friends, as PPE was virtually unobtainable. We were idly watching TV when these Neil Oliver episodes were repeated on PBS America. We had contributed some meadowsweet ale to this series, at the request of the production team and we looked forward to seeing it again. In the final episode about the Bronze Age Neil is seen walking around Dartmoor discussing villages. Then the camera cuts to Neil sitting in a pub discussing developments of this civilisation. We were shocked and surprised to see that the next sequence of him drinking beer from a beaker had been removed. However Merryn still appears in the credits.

I was so surprised at this, that for confirmation I bought the boxed set of DVDs to confirm that editing. On the second DVD at 1:51:35 he enters the pub, and then at 1:52:57 it cuts to him walking around Dartmoor again and the bit where he drinks from a beaker has been excised.

Back in March 2010, a member of the production team for this series approached us with a view to us providing them with some of our prehistoric beer. They wrote:

"While we figure out exactly when we might want to feature your beer in the series, I thought it might be a good idea to commission some from you, so that it's on hand when we need it! Would that be OK?"

We were delighted, at last someone was taking us seriously and we might get an opportunity to put the idea to a wider audience. So I replied:

"Graham here, the brewer. Yes I will make some meadowsweet ale for your programme. It will take about 4-6 weeks, longer if you want it to be very clear. At the moment I am waiting for more malt from my suppliers, and I will let you know when I start it. The name "meadowsweet" comes from the Saxon "medhu" for mead. The Saxons and the Vikings did not readily distinguish between ale and mead, and in fact meadowsweet ale tastes very much like mead. This kind of drink came to Britain with the first farmers in the Neolithic, as part of their package, and it was definitely drunk in the Bronze Age, Iron Age, Saxon era and Viking times, right through to the introduction of hops by the church in mediaeval times.

Regards."

The reply came back:

"Dear Graham,

Many thanks indeed for this email. Please could you send us the 2 litres of ale to arrive by next week? The address to send it to is:

Room MC5A4 BBC Media Centre

201 Wood Lane.

London

W12 7TQ

Please also let us know how we can pay you for the ale and the shipping costs. Thanks again and best wishes."

I replied:

"Hi, the ale and wort are in the post, and they should arrive tomorrow or Saturday. The postage was £8.22, so you could send a cheque.

The meadowsweet ale is free, as I can only give it away; customs and excise regulations prohibit the sale of home brew :-). However you could repay us for the ale by giving some exposure to our idea that "The first farmers in Britain brought not only cattle, cereals and ceramics, but also the skills to brew ale for their rituals and ceremonies. It came as a complete package." Also if you could please report to us any feedback or opinions on this idea that the other contributors to this production may offer.

We believe that this meadowsweet ale is not very different to that brewed in the Neolithic through the Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman Era (strong ale, slaves and hunting dogs were major exports from Britain according to Julius Caesar) and Viking times until the Mediaeval times when hops were introduced from Europe. Of course the Georgian industrial breweries were a major change.

The meadowsweet ale contains salycilates from the meadowsweet flowers and so should not be consumed by anyone allergic to aspirin.

Cheers.

Graham.

P.S. There still some 15 litres of ale left, so if you would like any more of this batch you should let me know soon!"

This reply came back:

"Hi Graham

Sorry about this, but could you send us another 2 litres so that we have 4 in total? We will of course pay you for this but have to do it by bank transfer so please send me your bank account details.

Please confirm this is all OK."

Thanks again.

I replied:

"Hi, yes I can send you another 2 litres, but the first opportunity now will be Tuesdays post, which should arrive Wednesday/Thursday.

I guess someone will have tasted it by now, any comments or feedback?

One thing I forgot to mention, ingredients. 15lbs crushed malt, 5 gallons of water, ½ oz dried meadowsweet flowers and 2 teaspoons of yeast. NO SUGAR, NO HONEY.

All the alcohol comes from the malt sugars from the barley malt, that is the wort.

That is also where most of the flavour comes from too!

I will send you the bank details when I know how much the second posting costs.

Regards."

We heard absolutely nothing more from the BBC team after that, except that I had to sign and return a form which stated that, "This beer is fit for human consumption." I did this and also added, with an impish sense of humour, "Sole intended purpose." So we waited for the series to be aired on TV.

Neil Oliver's series 'A History of Ancient Britain' finally aired on TV in 2011. We eagerly waited to see what they showed. In the fourth episode about the Bronze Age Neil Oliver is discussing villages, whilst walking around Dartmoor. The camera cuts to him entering a pub, and sitting with a pint of beer, discussing developments of that culture. Then it cuts to him sitting on a rock, drinking beer from a Bell Beaker. I could tell instantly that it wasn't my beer, because it was frothy and had bubbles in it. My beer was flat. So it must have come from a bottle or a can of beer. They did not use our beer. I often wonder if anybody even tasted it, or whether it was thrown away and poured down the sink.

There was no mention of us, or our work, but at least we were happy that the idea that 'beakers were for beer' was being promoted.

It could only be some powerful and influential archaeologists who could persuade the BBC to edit the beaker beer from that episode. We are quite accustomed to being ignored, and even bullied by some, but this a gross abuse of power and influence, for personal or political reasons, and it verges on totalitarian thought police.

The Achavanich Beaker

The Achavanich Beaker was found in Caithness, Scotland, in February 1987. Below is archaeologist Robert Gourlay's description of the site and also a pamphlet guide, with a map and illustrations. The words are the same in both documents.

| |

| Gourlay's report, page 1. |

|

| Gourlay's report, page 2. |

| |

| The Achavanich Beaker |

|

| Brochure, outer page. Folded in three. |

| |

| Brochure, inner page. Folded in three. |

This five page document was available online on the Highland Regional Council's web site as a PDF. I downloaded it on 15th May 2015, as at that time it was the best evidence for early beer brewing in Scotland. The pages were in a different order then, first the illustration of the Beaker, then the archaeologist's report, and then the illustrated brochure, inner first, and outer last.

Now, with the re-evaluation of the site by the Achavanich Beaker Burial Project, that document has disappeared. Only Dr Gourlay's report is available as a PDF. I have copies of the original five page PDF, if anybody wants it. Contact us please.

The report on the residues from the beaker make very interesting reading for any beer or brewing historian. The original report says:

"The contents of the beaker - no more than a slight smear on the inside - were analysed by palaeobotanist Dr Brian Moffatt in Edinburgh. His preliminary results suggest that the vessel originally held a mixture of the following:

(a) Prepared cereal - a course mixture of barley and oats with much chaff and stem. Judging from the still visible 'pour-mark' on the inside, it was a thin porridge or gruel.

(b) Honey - probably wild, it contains pollen from flowers which grew in a variety of habitats such as moorland, woodland, meadowland and pasture, scrubland, watersides, and even by the sea.

(c) Added flowers and fruits - presumably for extra flavouring. These include meadowsweet, bramble, and wood sage.

(d) The sap of birch and alder trees.

Dr Moffatt concludes: 'There are here multiple bases for fermentation, and the outcome of collecting them would be an "alcoholic hotchpotch".' This then, could have been the earliest known alcohol from Caithness' "

I don't know why, but there seems to be a concerted crusade against Beakers being used for ale or beer. This aspect of the contents of the beaker seems to be controversial, perhaps even unacceptable to some archaeologists.

The burial, the beaker and its' contents were recently re-evaluated by Maya Hoole and a team of archaeologists, including Dr Scott Timpany of the University of the Highlands and Islands who did the pollen analysis. The conclusion was that the beaker contents were purely medicinal. This was based upon the identification of Meadowsweet and St John's Wort pollen. See here for a summary of the Achavanich Beaker Burial Project's findings. Please note that there is no longer any mention of cereal residues or alcohol.

Both Meadowsweet and St John's Wort are gruit herbs, they were traditionally used to preserve ale and beer.

The fact that Brian Moffat's pollen analysis differs so much from Scott Timpany's could be explained by the pot being contaminated by background pollen since it's excavation. It has certainly been around quite a few places since it was first found. Moffatt had the benefit of working on the pot when it had been freshly excavated. Timpany's analysis conveniently excludes the cereal residues.

It is important to consider that some archaeologists are primarily sociologists and not scientists and sometimes make unwarranted assumptions. The active ingredients in Meadowsweet and St John's wort are alkaloids, and are only soluble in alcohol and not in water. The term alkaloid is derived from the word alcohol, itself an Arabic word in origin. By eliminating alcohol from the contents of the beaker their interpretation as purely medicinal has been rendered impossible. They have shot themselves in the foot!

Many traditional herbal remedies and medications are based upon the alkaloids in their herbs, and these preparations are all alcohol based. Many of the specialist ancient Egyptian brews were medicinal.

Balfarg/Balbirnie

One of the largest and most important prehistoric ceremonial sites in eastern Scotland is known as Balfarg/Balbirnie and the Balfarg Riding School excavations. According to Canmore, the National Record of the Historic Environment of Scotland:

"These two sites (Balfarg and Balbirnie), along with structures that were

found between them, form one of the most important groups of monuments

of neolithic and bronze age date in eastern Scotland. The visible

monuments are a henge and a small stone circle, now re-sited to the

south-east of its original position; excavations between them have,

however, revealed a ditched enclosure, two timber structures, cairns and

burials as well as a large quantity of pottery."

See https://canmore.org.uk/site/29990/balfarg and https://canmore.org.uk/site/29959/balfarg-riding-school for all the details.

| |

| Plan of excavations at Balfarg, Balbirnie and Balfarg Riding School |

Map: Barclay and Russell-White, G J and C J eds 'Excavations in the ceremonial complex of the fourth to second millennium at Balfarg/Balbirnie, Glenrothes, Fife', Proc Soc Antiq Scot, vol. 123, 1993, page 50

It was an extensive site, now a housing estate, and spanned from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. There was a henge, two stone circles and two rectangular timber structures. Many Grooved Ware pottery sherds from large pots were found there and two of them, 63 and 64, had residues in them.

This is what interests us, as brewing historians.

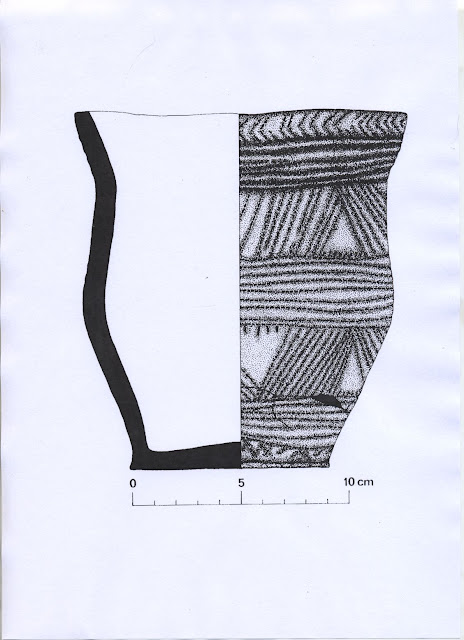

| |

| This a composite image, formed from pages 101 and 103. The scales have been preserved. |

Merryn had been studying the archaeological literature on Bronze Age Beakers for residues indicative of beer brewing. When she read the descriptions of the residues on these two sherds of Grooved Ware, it was a light bulb moment for her. I can remember how excited she was at finding similar residues to those in Bronze Age pots to the ones from the Neolithic.

This meant that the Neolithic people had probably been making malt and ale too. An idea that is still controversial, even 22 years after she submitted her M.Phil Thesis "Barley, Malt and Ale in the Neolithic", available in full on her Researchgate page. To make it easier to access, Merryn has put the Introduction, Summary and Discussion and Conclusions as blogs, entitled 'pieces from my thesis parts #1, #2, #3'. Follow these links if you are interested. There may be more to come.

Some archaeologists still reject this idea of beer, and they will not incorporate it into their interpretations. For example, the archaeologists currently excavating at the Ness of Brodgar refuse to discuss it with us. Maybe this is because they are theoretical sociologists, formerly known as post-processualists, and find the topic to be too scientific and technological to understand.

Brian Moffatt's analysis of the cereal based residues in 63 and 64 is that they contained;

"Processed cereal, both barley and oats, with meadowsweet, pollen and macroplant. Sample 14 had clumps, indicating a flower head of meadowsweet."

There are other things that he identified in the residue, such as minute droplets of beeswax, fat hen pollen and even small amounts of solinaceae (hemlock family) pollen.

|

| Encrustation on the outside of a sherd from pot 63. Illustration from Gordon Barclay's booklet 'Balfarg:the prehistoric ceremonial complex' published by Historic Scotland, page 17 |

Interestingly, on the outside of a sherd of pot 63 Moffatt found an encrustation with black henbane pollen and broken henbane seeds in it. He says that black henbane can be used "to procure sleep and allay pains". This property of henbane has been known about for a long time, for example, from a Babylonian cuneiform tablet ~ 2250BC.

Brian Moffatt suggests that henbane can be applied topically or that it can be ingested. Ingesting henbane is very dangerous. It takes about 50% of the lethal dose to effect pain relief. The concentration of the toxins varies widely, both between plants and even within the same plant, as much as 6 fold or more. The only safe way to take henbane is by inhaling the smoke from the seeds, then it is easy to stop when the correct level has been achieved. Scribonius Largus, the physician to the Emperor Claudius, writes of the use of henbane in his Scriptorium Medicantorium, by placing henbane seeds on a hot plate of metal and inhaling the fumes. Mediaeval physicians also write about driving out the "tooth worm" with the fumes from burnt henbane seeds.

A broken pot sherd would be very good as a substrate for heating a henbane paste for the inhalation of the fumes. This could easily explain the presence of henbane seeds in the encrustation on the outside of the pot 63 sherd from Balfarg.

Interestingly henbane seeds were also found at Skara Brae, the Neolithic village on Orkney.

Henbane can also be a used as a hallucinogen. It seems that the thought that "hallucinogenic practises" had been performed at the ceremonial Neolithic site at Balfarg incensed some archaeologists. They quickly assembled a team to discredit Moffatt. This resulted in the rapid publication of an article in the Journal of Archaeological Science, by Long et al in 1999. I can't find a copy available other that the 'pay to view' paper here.

In their paper "Black Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger L.) in the Scottish Neolithic: a reevaluation of Palynological Findings from Grooved Ware Pottery at Balfarg Riding School and Henge" they made one fatally flawed assumption. See the underlined sections below:

"These residues occur as hard concretions that can be quite thick. They are assumed to be residues from the contents of the pottery vessels used in activities at the henge monument. One difficulty with this interpretation is the high frequency of residues adhering to the outside of the vessels (see table 1). These may be residues from spillage or boiling, but their location on the exterior surfaces means that the relation between the vessel contents and the crust is not a direct one." (see page 46)

If you have enjoyed reading this and would like to discuss any of the issues, please comment below.