The brewer bought these books in 1982 when he got his own house. Before that, he'd only used beer kits which are basically just a large tin of malt extract. That's all you can do in a shared house with a communal kitchen. Extract brewing. Since 1982 he has brewed nothing but all-grain beers, starting off by following Line's recipes in detail, making mistakes along the way and learning from them. Over the years he has adapted them and now has a brewing recipe of his own that combines different aspects of these traditional beer recipes. First, mashing in some crushed pale malt, then lautering and sparging to obtain the wort, adding treacle and dark brown sugar for colour and flavour in the boil. Sometimes, but not always, porridge oats are added to the mash tun. Hops are used, usually Goldings, Bramling Cross and Fuggles. He's made ancient style ales, when the wort is not boiled, a raw ale. Dried meadowsweet flowers were added for preservation and flavour. The recipe was based upon the analysis of residues on a Bronze Age beaker from Strathallan, Scotland.

Line's recipes reflect the brewing industry of his day. There is no mango puree or other novel additions to his recipes, as craft brewers do today. There are some added sugars, specialty roasted malts and a couple of Line's recipes use malt extract. The transformation of grain into ale is a multi step process: malting, mashing, obtaining a wort and fermenting. It's easily possible to get all the fermentable sugars you need from the malt in the mash tun, when you know how to do it. There is no need for adjuncts or extras in the mash tun unless you want to add them.

The advent of modern craft brewing in the USA in the 1980s has changed the brewing industry. A wide range of innovative adjuncts are now being added to the mash tun. Many people have asked the question: what is craft beer? It seems to be quite a difficult thing to define. Some modern craft brewers use extracts and syrups, adding all sorts of unusual ingredients, such as peaches, mangoes, chillies or chocolate. That's fine. Other craft brewers are all-grain brewers, starting with crushed malted grain in the mash tun and adding their novel extra ingredients to that. That's also fine. The aim is to make good, unusual and innovative beers. Some craft brewers are small businesses, producing their beer for the local market. Others are huge breweries, producing vast amounts of beer for the global market. I'll leave my attempt at defining 'modern craft beer' there. It's a confusing thing.

When I began to investigate the archaeological evidence for beer brewing in the Neolithic and Bronze Age (back in 1996) I started from a practical, scientific and technological point of view. I wanted to understand how beer is made from grain. What's the science behind it? What techniques and skills does the brewer need? The obvious place to start was The Big Book of Brewing. I read the mashing chapter several times and, after that, I went on to study the more complex and detailed work of brewing scientists. My approach was this: if I wanted to recognise and appreciate the evidence for beer brewing in the archaeological record then I needed to understand the fundamentals of the beer brewing process. I was not going to completely rely upon the anthropological or archaeological literature.

mashing

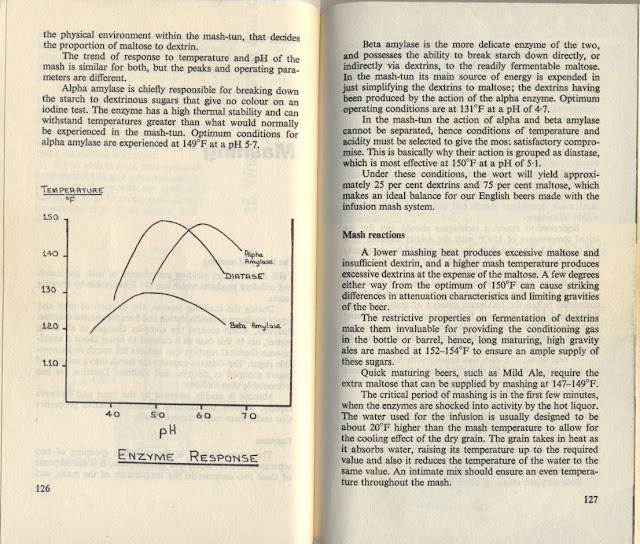

This is something that only an all-grain brewer does. It's the saccharification process. When making malt, enzymes are activated in the steep and on the malting floor. These enzymes, alpha and beta amylase, are kept viable by the maltster during the careful, slow drying process in the kiln. In the mash tun, these same enzymes re-activate and, at the right temperatures, they convert the grain starch into malt sugars. Here's a technical explanation of mashing by David Line in the Big Book of Brewing. I've been to quite a few archaeology conferences over the years, given presentations and said that this is an excellent book if you want to understand how to mash the malt and make a beer from the grain. It usually raises a laugh from the audience. I don't know why.

|

As mentioned in the previous post, we buy in our malt. We have no facilities to make it. We do our mashing in a modern plastic mash tun, using a grain bag. There are two boilers, one for the hot water which always necessary when beer is being made. You need it for sparging. The other is for boiling the wort. Our mash tun has an electric heater, so we heat the water for the mash in there until it reaches around 74 degrees Centigrade. That's the right temperature for the 'strike' when the crushed malt is added to the hot water. As Dave Line explains above, striking chills the water to 65 degrees Centigrade. Perfect for the enzymes to work.

|

| the strike: crushed malted barley meets hot water |

The crushed malt is left in hot water for about an hour. We put a sleeping bag over the mash tun to keep the temperature stable for the starch converting enzymes to get to work. After about an hour, they have done their job and we have a mash tun full of sweetness. The mash is brown, no longer the pale crushed malt we started with. When the lautering and sparging is finished and we have our wort, the grains in the mash tun look as if they are whole. They are not. Only the husks remain. The starchy endosperm has all been converted into malt sugars by the enzymes. This leftover grain is draff, also known as spent grain or brewer's grains and it makes excellent animal fodder. One of the reasons why the archaeological evidence for mashing is minimal.

|

| spent grain, after mashing, lautering and sparging |

our mashing experiments and demonstrations

Fire is the obvious way to heat a mash in a sealed earthenware pot, but you have to be careful - too much heat and the saccharification will not work. I made a hearth in our back garden and decided to find out whether I could mash in a pot. Here's a couple of photos of my first mashing experiments. Almost twenty years ago now. This work was done as part of my M.Phil research into the archaeological evidence for brewing in prehistory. I took some crushed pale malt and mixed it with cold water in an earthenware bowl. The porous bowl had been previously sealed with beeswax. I put the bowl on hot ashes to provide a gentle, consistent heat. I decided to start with cold water. The reason being that I could watch over the pot and wait for the correct temperature for the saccharification as the water slowly heated up.

|

| a starchy start to the mashing process |

With no thermometer how would I know when the temperature was correct for mashing? This, in practice, turned out to be very easy. The mixture in the bowl began to smell sweet and delicious. The mash changed colour. I tasted it. It tasted sweet. The saccharification was obvious. While I watched the mash pot I made some little 'cakes' or 'biscuits' by making a thick mixture of crushed malt and water. These were put on the flat stone beside the fire. It had become quite hot by now. Splashing water on them occasionally to keep them a bit damp, it was again obvious that sugars were being made. I knew that the enzymes were transforming starch into sugars. I understood the technology and the science. In prehistoric times this transformation of inedible grain into sweetness was, perhaps, deemed to be magic.

|

saccharification in the bowl and sweet barley cakes on a hot stone

|

We've done several

demonstrations of this 'mashing in a bowl' technique. A couple of times a year we used to work in Hut 7 at Skara Brae, showing

visitors that there is more to neolithic grain processing than just

making flour, bread, porridge or gruel. Fires are not allowed in the replica hut, for

obvious reasons. We overcame this by having a mash we'd made at home earlier. We put it in a bowl on the central hearth,

surrounded by samples of modern barley, bere, crushed malt, wort and

beer. The mash smelled delicious, people came in to see what was going on. It's much easier to explain the brewing process to people when there are samples available, to smell and to taste.

The most enjoyable event so far was the one I did at Eindhoven Open Air Archaeology Museum in April, 2009, as part of a small beer brewing meeting organised by EXARC. The mashing

was very successful, being caramelised by the end of the day. Visitors to the museum

'stole' some of the sweet biscuits made on hot stones and ate them. Those who tasted the mash

said it was delicious. The medieval brewers who had done a demonstration the day before were impressed at our mash in a bowl.

|

| A caramelised mash in the bowl, sweet barley 'cakes' by the hearth |

tub and trough mashing

The shape of the mash tun isn't important. Mika Laitinan explains how Sahti brewers traditionally use both tubs and troughs for mashing and lautering. The ancient tradition of farmhouse brewing in northern Europe still exists in some areas today. Techniques are handed down from one generation to the next. A few years ago I was not aware of this traditional all-grain brewing. I certainly know about it now. I reckon anyone interested in ancient beer brewing should take note of this tradition and study the farmhouse brewing techniques.

In our experimental work we were inspired by archaeologists Declan Moore and Billy Quinn of the Moore Group, based in Galway, Ireland. They did a trough mashing demonstration at the 8th World Archaeology Conference in Dublin in 2008. I realised that I was simply not making enough mash in my small earthenware bowls. These guys did the job properly. It was a spectacular demonstration of one of the functions of a burnt mound and trough - as a mash tun. Follow this link for more details.

We've mashed in a wooden tub, using hot stones to heat the water and maintain mash temperature. Below, a couple of photos from the mashing demonstration we did at an Ancient Technology event for the Orkney Archaeology Society, organised by local potter Andrew Appleby in 2010. We heated the water with hot stones, adding crushed malt when we could see our reflection in the hot water. This is an old technique for judging when the water temperature is correct for the strike, before thermometers were invented. It works. We used the hot stones to maintain mash temperature. It all worked perfectly.

In our experimental work we were inspired by archaeologists Declan Moore and Billy Quinn of the Moore Group, based in Galway, Ireland. They did a trough mashing demonstration at the 8th World Archaeology Conference in Dublin in 2008. I realised that I was simply not making enough mash in my small earthenware bowls. These guys did the job properly. It was a spectacular demonstration of one of the functions of a burnt mound and trough - as a mash tun. Follow this link for more details.

We've mashed in a wooden tub, using hot stones to heat the water and maintain mash temperature. Below, a couple of photos from the mashing demonstration we did at an Ancient Technology event for the Orkney Archaeology Society, organised by local potter Andrew Appleby in 2010. We heated the water with hot stones, adding crushed malt when we could see our reflection in the hot water. This is an old technique for judging when the water temperature is correct for the strike, before thermometers were invented. It works. We used the hot stones to maintain mash temperature. It all worked perfectly.

|

| heating water with hot stones |

|

| the strike |

About ten years ago when I was working as a tour guide at Tomb of the Eagles/Liddle Burnt Mound, Orkney, we did a small trough mash for the Orkney Tour Guides Association. The brewer had made a small wooden trough specially for the event. The sweet, delicious aroma of the mash brought people to our demonstration behind the Visitor Centre. They were curious. What was that lovely smell? Some tasted the mash and were surprised how sweet it was. That's the saccharification, we told them, we're making malt sugars. There are more photos of the event here.

|

| mashing in a wooden trough, checking the temperature |

| ||

| the mash in the stone trough at Bressay, grains have sunk to the bottom, the wort is clear to see. |

a bit on fermentation (as promised)

Yeast converts sugar into alcohol. There are many different sorts of yeast so it's quite important to get the right one. If not, all that work to obtain a wort will be wasted. There are several ancient options.

In Ancient Egypt it seems that sweet wort was fermented in large pots. Using a scanning electron microscope Dr Delwen Samuel has identified yeast on the internal surfaces of large pots from Amarna, Egypt. Dried yeast inside a pot would work well to start a fermentation and this technique could have been done in any part of the world where pots were used as fermentation vessels.

Another option would be to stir the fresh wort with a stick that had been used to stir the previous ferment. This may sound strange, however, such a practice is recorded in histories of the Western Isles and the Hebrides. The brewer experimented with this technique using a wooden spoon to stir a fermenting brew. He hung the spoon up to dry, then stirred a fresh wort. It worked. Details here.

Yeasts can be cultivated and stored. The traditions of the farmhouse brewers include keeping a dried yeast as a starter. I admit that I am no expert on this. Yeasts and alcoholic fermentation is such a huge subject and I tend to focus on the malting and mashing parts of the brewing process. The world of all-grain brewing, as well as yeast specialists, have recently been amazed at these farmhouse yeasts from northern Europe. The place to read about them is here, where Lars Garshol explains about some of his extensive work on researching and discovering the farmhouse yeasts and ales.

Lambic beers are famous all over the world. The wort starts to ferment because there are wild yeasts and bacteria within the brewery. The resulting beers are aged for several years and are often sour, so fruits can be added to sweeten the brew. Here's a short definition of lambic beers, more information here.

"Belgian Lambic beer is left in open vats where wild yeast and bacteria

are encouraged to take up residence. In fact yeast is never added

directly to the wort. Instead wild yeast that is unique to the region is

simply allowed to fall into the vats in a process known as spontaneous

fermentation."

Finally, a word about spontaneous fermentation. I was once told that it's possible to ferment a beer by 'brewing under a tree'. Some people think you can just leave the wort to 'catch a wild yeast'. Be very careful if you do this.

You might catch the wrong one.

FURTHER READING

- A bit more on fermentation - there are very many kinds of fermentation and most of them are not alcohol producing. Think of sauerkraut, yoghurt, food preservation etc. It's a huge topic. See Steinkraus: Handbook of Indigenous Fermented Foods if you have access to a University Library. It's an expensive book and a thorough study of the subject. If you don't have the luck to get into a University Library, then there's this paper available online 'Fermentations in World Food Processing' also by Professor K.H. Steinkraus.

- More on brewing techniques - you might like to read this post on farmhouse brewing by Lars Garshol. There are some very clear descriptions of the brewing process and great photos to show how beer brewing has been done for generations in Estonia. As they say, a picture speaks a thousand words.

- Could the Natufians, the earliest agriculturalists of the Fertile Crescent over ten thousand years ago, have made malt and ale? Did they have the technology? Thomas Kavanagh (1994) discussed this in Brewing Techniques magazine. "Archaeological Parameters for the Beginnings of Beer"

- Finally, my published research papers and my M.Phil Thesis (2004) can be found on Researchgate and downloaded for free.