I should have presented this paper at the World Neolithic Congress in Turkey, November 2024. My abstract was accepted by the scientific committee and the presentation was eventually included in session G11. However, I was not able to attend the Congress. So I have submitted the paper to PAST, newsletter of The Prehistoric Society, and it was published last month in the November issue.

This will be appearing online soon and I will provide the link when that happens.

Here it is:

https://www.prehistoricsociety.org/publications/past/111

The importance of being malted: making malt sugars from cereals in the Palaeolithic.

Published in PAST, Autumn Issue of The Prehistoric Society Newsletter, 111, pages 12 to 14.

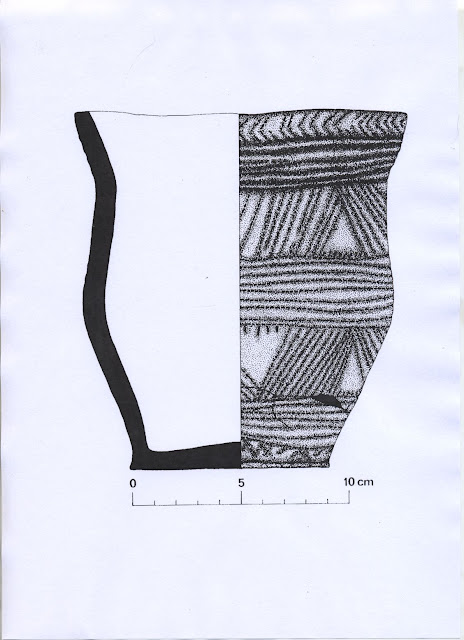

In 1953 archaeologist Robert Braidwood initiated an important debate: what began the domestication of cereals in the Ancient Near East? Was it for bread or for beer? Although malt and malting was discussed briefly by some of the Braidwood Symposium participants, the "Bread or Beer" debate continues, unresolved, today.

The important thing about cereals, such as wheat, barley, rye and oats, is that they have a unique property. They are a source of malt sugars. Any grain, ancient or modern, can be transformed into sweet malt sugars by the simple processes of malting and then mashing, or mixing, the crushed malt with hot water. Malt and liquid malt sugars are the basis of making ale and beer in any era.

Given that the first aspect of the ale and beer brewing process is the manufacture of malt sugars, perhaps the wrong question is being asked. Maybe the question should be who were the first maltsters? When was this special and remarkable property of the grain discovered? There's good evidence that this happened in the Palaeolithic, in the lands where barley and wheat grew as wild plants and when people were hunter-gatherers.

Malt is mysterious to most people in the 21st Century. The ancient craft of floor malting has become industrialised, with malt now being made in huge germinating kilning vessels for a global brewing and distilling industry. Until a couple of hundred years ago, however, making the malt for brewing ale and beer was a common, locally based activity. Every village and town had at least one maltings. Malt was made on large farms and farmsteads and was a familiar agricultural activity, as it has been for thousands of years.

In England today there are only three commercial floor maltings left: Thomas Fawcett & Sons of Castleford, Yorkshire, Crisp Malt Ltd at Great Ryborough, Norfolk and Warminster Maltings (Britain’s oldest working floor maltings) in the west of England. We were told by seventh generation maltster, James Fawcett, that floor malting was once known as the ubiquitous craft: it was everywhere and omnipresent.

In the archaeological literature, the words germinating, sprouting and malting are often used indiscriminately, as if they all mean the same thing. This is not the case. Germination begins within the grain, as enzymatic and biochemical changes, before any external growth occurs. Sprouting is uncontrolled germination, as the plant grows roots and green shoots on the way to becoming a plant. Malting is the carefully controlled and complete germination of the grain, without sprouting. The last thing any maltster wants to see is green shoots. This means the malt is 'overshot' and is not good for making sugars.

The first step in making malt is to soak the grain, taking care not drown it by leaving it too long in a container of water. Grain is a living thing and must be treated accordingly. Ideally, leave the grain in a tightly woven basket in a bubbling stream. This way, it has the oxygen and water it needs to begin growth. At first, two tiny bumps appear. This is known as chitting and is the initial growth of the rootlets and coleoptile, the precursor to the shoot.

We have been asked whether grain was different in the past. The answer is, yes, there are some differences. Wild grains were a lot smaller and thinner with a much thicker husk, however, the fundamental germination biochemistry remains unchanged. Grains still germinate and grow in the same way that they did thousands of years ago.

Once chitted, the malt is laid on a suitable floor and regularly turned. Shoots of any plant grow upwards. The regular turning of chitted malt confuses the geotropism of the coleoptile and it does not develop into a shoot. Turning also prevents rootlets from becoming entangled, maintains an even temperature and inhibits mould. When the grain is soft and is easily squished into a doughy ball, it is ready to use, or to dry for storage. It must be dried slowly, gently and with care, to avoid destroying the starch converting enzymes.

Harvested cereals must be stored dry if they are to keep well and to prevent mould. The same applies to malt. Superficially dried malt might resemble unmalted grain, however it has totally different properties. Malt is friable. It is easily crushed into husks, fine flour and fragments and, most importantly, it has the potential to make malt sugars.

Crushed malted barley, Maris Otter. Malt is friable, very easy to crush with a stone and has the potential for making malt sugars.When crushed malt is mixed with an abundance of hot water in a container and kept at around 67 to 65 °C for an hour or more, the amylolytic enzymes digest grain starch into malt sugars, as sweet as a synthetic honey. Today, this biochemical process is called mashing. Containers are useful for mashing, but not essential.

As part of her research for an M.Phil, “Barley Malt and Ale in the Neolithic”, Merryn made malt sugars without a container. As well as mashing in an earthenware bowl (sealed with animal fat), she mixed some crushed malted barley with cold water and put this mixture onto a hot flat stone beside the hearth, liberally sprinkling it with water as they warmed up.

These techniques produced a sweet mash and delicious sweet malty biscuits.

Merryn's back garden mashing experiments: making sweet malt sugars from crushed malted barley as part of her M.Phil Thesis, 2004So, malt is a very important, often overlooked product of the grain. A malting floor can be made of beaten earth, clay, lime plaster or even a dry cave floor. Caves are ideal for making malt. In Nottingham, England, caves have historically been used for malting. The cool, even underground temperatures allow for malt to be made all year round rather than stopping in summer because conditions are too hot.

The Nottingham Cave Maltings made us consider the hunter gatherers of the Palaeolithic Ancient Near East who lived in caves. We studied many excavation reports. One that stood out was entitled “Cooking in Caves: Palaeolithic carbonised plant food from Franchthi and Shanidar” by Dr Ceren Kabukcu and colleagues. The authors analysed carbonised macro-remains of processed plants from Palaeolithic layers in the Franchthi Cave in southern mainland Greece, and Shanidar Cave, on the western flanks of the Zagros Mountains.

The authors concluded that there was diversity and complexity of plant use and preparation at both sites, based upon the condition of the plant microfossils that they found. People were processing the locally growing wild pulses, nuts, grasses and cereals using several different techniques, including crushing, pounding and grinding as well as soaking, steeping and mashing.

Although many things were made from pulses and nuts, some of the carbonised food fragments resembled charred bread-like foods or finely ground cereal meals, similar to those found at Neolithic and later prehistoric sites. Malted grain would make sweet attractive products.

In 2007, Professor Gordon Hillman and Ray Mears made a TV series, and accompanying book, “Wild Food”. The programmes are available on You Tube and they are well worth watching. They show how to gather wild seeds and process them into biscuits or bread-like products.

These experiments were based on Hillman's study of grain processing techniques in Islamic countries, in which the making of malt is now prohibited. As such, the grain was parched which rendered it incapable of germination for malt but this need not always have been the case. Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers of the Ancient Near East lived in caves, they posessed knowledge of fire and basket weaving and had access to wild cereals. It would not be difficult for them to discover that soaking wild cereal grains in a basket in a stream until they chitted made them much easier to process.

Perhaps it wasn’t always possible to dry the chitted cereal in the sun. We can imagine that, when it rained, people took wet grain into the cave, lay it on the floor, perhaps turning it with a scapula (a perfect tool for the job). Then after several days when the rain stopped, it could be dried in the sun. This malted and fully germinated, but minimally sprouted grain would then have had the potential for making attractive malt sugars.

The discovery of this important and special property of the grain would develop over the millennia into the massive global malting industry that we see today.