Kilns and ovens are usually considered to be very hot places, for example, where pottery is fired at a high temperature or bread is baked in a hot oven. Grain drying kilns are not like this. In most of the academic archaeological literature, grain is 'parched' in a kiln or maybe the malt is 'roasted' prior to brewing an ale or a beer. The idea of "parching the grain" and "roasting the malt" are archaeological myths and have no place in the reality of drying a harvested grain or making a base malt.

When grain is 'parched' at a high temperature the seed corn for the next year is killed. When malted grain is 'roasted' the enzymes are destroyed and it will be useless in the mash tun.

Here's one of the most frequently used images of it, from the BBC news page report.

I'm impressed by the quality of the stonework. Whatever the function of this feature, it was very well built. It was heated by a fire on a regular basis, as can be seen from the blackened earth, in the entrance of the kiln.

So what was it? What kind of medieval industry would have used something like this? Was it a part of the malting and beer brewing process? Or was it something else?

For me, it's a frustrating picture. I want to see more of the context and the surrounding archaeology. I have lots of questions. Was any grain found nearby? If so, was it examined to identify partial germination, otherwise known as malting? If this was a malt kiln, which is of course a possibility, then where was the malting floor? And were there any steep tanks? Steeping facilities and malting floors - these are essential installations for the manufacture of malt. Without them, you cannot make malt.

To describe this stone built feature as 'a malting oven' is, however, not the correct technical name.

Within the traditional trade, craft and industry of malting, they are called malt kilns. Another description could be a grain dryer or corn dryer, used to dry the harvested oats and grain as well as to dry the green malt from the floor. It's an important point. If you don't use the correct terminology for a craft, then perhaps you are not familiar with the technical details and everyone gets confused. This applies to any craft, technology or skill based activity - when discussing or interpreting the archaeological discoveries that relate to it, the correct jargon should be used.

The only place I find "malting ovens" referred to is in the scholarly literature of archaeology, anthropology and history. An installation that has been interpreted and described as a 'malting oven' infers that the malt is actually made in the oven, that you can just put a heap of barley into an oven, heat it up and then, hey presto, you have malt. In many of the news reports about this particular medieval discovery in Northampton, there is someone saying that malt is made by 'roasting the barley in an oven.' It's a common misconception.

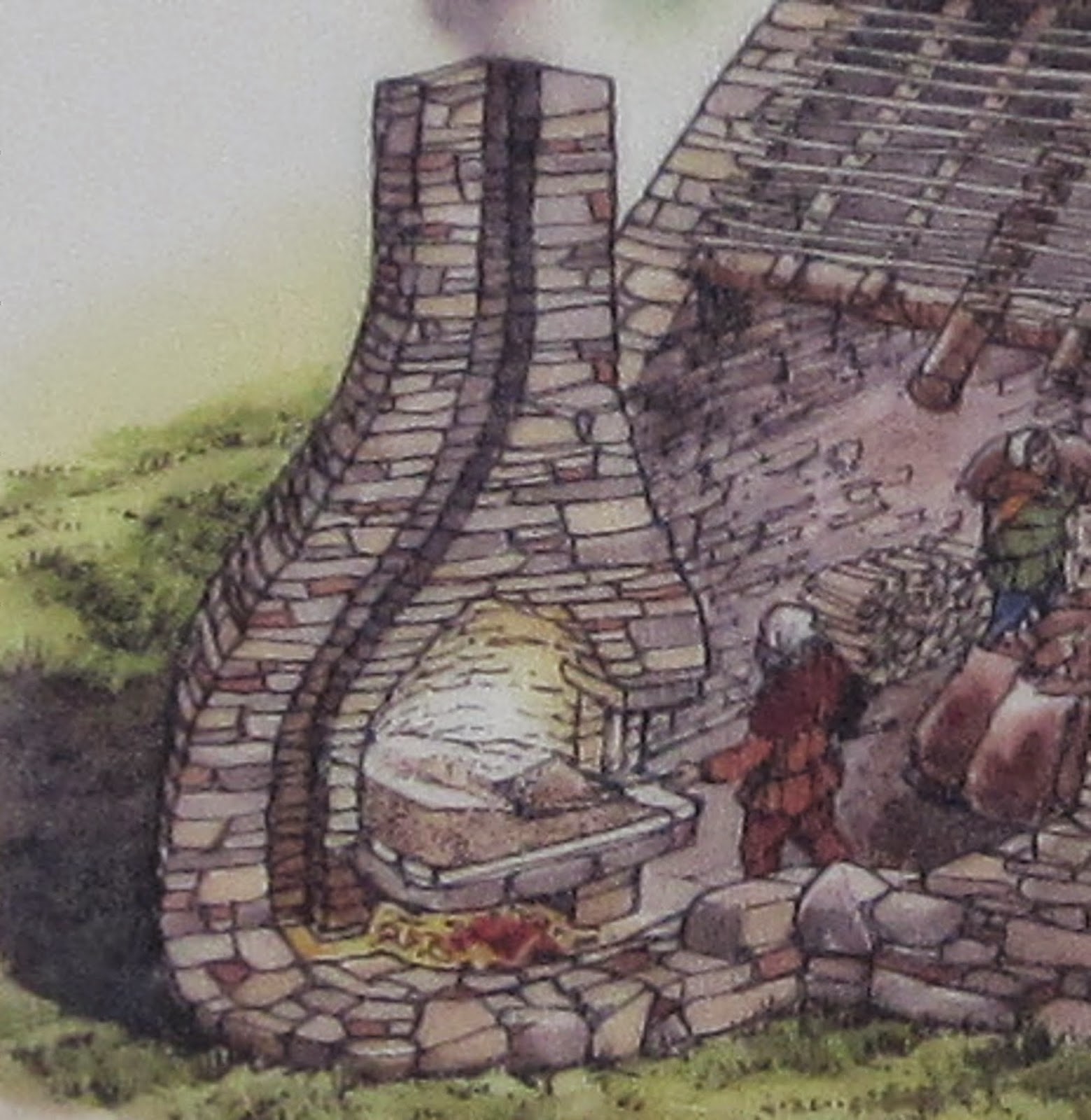

Here's a photo of an artist's impression of grain drying, from one of the information boards at Jarlshof, Shetland. This an archaeological site with evidence of stone buildings that span over 4000 years, from the Neolithic to the late medieval. The picture is supposed to illustrate 'how grain is dried in a corn drying kiln'. Every detail is wrong.

|

| Not how a malt kiln or grain dryer works. |

- you can't dry damp grain or malt by heating it on a solid floor with a fire beneath. You will end up with hot wet grain.

- there needs to be a permeable floor for the wet grain or malt to lie on, so the warm air passes through the grain bed.

- the fire is not lit directly beneath, but at a distance. A long flue conveys warm air from the fire to the bowl of the kiln. The warm air rises through the bed of grain or malt, drying it gently and slowly.

- the reason for a long flue is to prevent sparks from the fire from setting the almost dry grain or malt alight. Malt kilns do not have a chimney, as this illustration shows. There is a wide opening at the top.

- it is essential to dry the malt slowly and gently over several days. The direct heat of a fire is too hot and would 'kill' the malt. Instead, you need warm air to dry the malt.

Malt is not the same thing as roasted barley.

In the academic archaeological and anthropological literature, I have come across the idea that ale and beer can be made from roasted barley. Over the years, I have done lots of demonstrations about how the malt and ale are made and it seems that lots of people think this. Sorry to disillusion you, but it is not possible to make ale or beer from roasted barley. It can only be used as an adjunct, for flavour and colour. It is not a base malt and cannot provide any sugars in the mash tun because it has been roasted, thereby destroying the enzymes that convert starch into sugars.

In medieval terms, the germ of the grain has been killed by roasting.

Specialist malts, also known as coloured malts such as crystal, amber, roasted or chocolate malt, are a feature of modern, not medieval brewing. They have only been around since the early 19th Century. Specialist malts are dried or roasted at a much higher temperature than base malt and are used for the colour and flavour of the beer or ale. They do not provide any of the necessary fermentable sugars. That comes from the base malt.

Grain drying and malt kilns

There is another popular misconception. Because they are called kilns, it is often assumed that they have to be run at a high temperature, like a pottery kiln or a kiln for making bricks or roof tiles. This is not so. High temperatures kill the malt.

A typical grain barn is a long, rectangular stone building with a circular kiln at one end. The fire is lit in the fire hole and the warm air, and the smoke, travel through the flue and pass through the bed of grain which has been spread on a lattice of sticks in the bowl of the kiln. You would certainly not want to light any fire directly beneath that.

|

| wet grain is spread out on a lattice of sticks, woven together. see here for more details |

In an earlier post, I wrote about traditional grain barns and grain dryers and on how they worked, focusing mainly on the Corrigall Farm Museum, in Harray, Orkney. I'm really lucky where I live, because on Orkney there are quite a few surviving grain barns and grain dryers, some of which date might back to medieval times. Most are fairly ruined and none of them are used any more.

Graham took some photos of an old grain drying kiln at Houton, Orphir, Orkney a few years ago. We are not sure of its' precise age, but it is typical of many such buildings on Orkney and Shetland. We think they should be preserved and treasured as part of agricultural history.

|

| the ruins of a grain barn, with kiln, at Houton, Orphir, Orkney. Photo by Graham Dineley |

|

| the barn is fairly ruined but the kiln is mostly intact - it's very well built |

| |

| looking down into the bowl of the kiln, with the flue just visible on the left |

|

| looking up |

|

| this is the stone 'shelf' upon which the lattice sits, the hole is where the dried malt is raked out |

I'll end this post with a ground plan, because all archaeologists like ground plans, of a traditional Orcadian farm house, byre, stable, grain barn and kiln, from John Firth's book "Reminiscences of an Orkney Parish". I hope it shows what I mean - that the kiln fire is not directly beneath the grain.

Fantastic article! Extremely informative and interesting. I am starting to make my own grain and this was a very cool look into the history of malting grain. I feel encouraged to fallow in the footsteps of my forfathers and continue the tradition. I don't believe the picture showed a malting kiln.

ReplyDeleteThanks very much for this post. I am writing about coal mining in the Yorkshire Dales. They supplied coal and coke from Wensleydale to the Richmond and Bedale areas in the 16th and 17th century. I have been trying to decide whether or not they used coal for malting barley, presumably not from your post. They started making coke (cinders) about 1630, there are direct records in 1663 though this reference was in smelting lead. This was a period when reserves of wood as a fuel were diminishing fast in the area generally.

ReplyDelete