|

| a sticky sweet spoonful of malt extract (photo: healthysupplies.co.uk) a modern product |

Malt extract is considered to be very good for you - it's an added ingredient in many breakfast cereals. When I do demonstrations, I always take a jar of malt extract for people to taste. They are reminded of their childhood, and of eating a spoonful every day, for the B Vitamins.

Malt extract is made by boiling wort in a vacuum and the technique was only discovered in the late 19th Century AD. Oh, and there is malt vinegar as well. And malt loaves. Many brewers use a liquid or a dry malt extract. Known as LME and DME, it's a main ingredient of beer kits in the 21st Century. Malt extract is also important to the modern food processing industry, particularly so in the USA it seems.

Prohibition forced maltsters to think of a different way to process and sell their malt, other than as alcoholic drinks, like beer and whisky. Prohibition was the death knell to many American breweries in the 1920s.

It's no wonder that so many people are confused about malt.

|

| malt whisky. nice but not neolithic |

| |

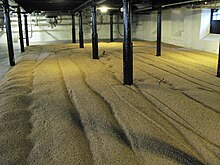

| malt on a traditional malting floor |

For me, 'malt' means partly germinated grain which has been carefully dried for further processing by brewers and/or distillers. It is traditionally made on the malting floor. The grain has been steeped and aerated, then it is spread out on the floor in a cool, dark, well ventilated building to begin to grow. Once the rootlet and shoot begin to show, it is gently dried in a kiln. We had been talking about two very different things. As part of writing this blog, I checked the Encyclopedia Britannica for its' descriptions of what malt is, how it is made and what it is used for.

Much of the detail is correct, but there are a few salient details omitted. For example, there is no mention of the air rests that are an essential part of the steeping process. If you just leave the grain to soak or steep without air rests, then the grain will be killed. It will, effectively, drown. Ancient and traditional techniques include leaving the grain in a bag in a shallow stream. This provides the essential oxygen and water for the germination process to begin. Modern methods use huge steep tanks.

Grain needs both water and oxygen to begin germination. If the steep is not aerated, then it will not take long for the water and grain to smell horrible and for the grain to be bad. It will not begin to germinate, you will not have any enzymes to convert starch into sugars and you will not be able to make ale. Or beer. Or whisky.

In the first stages of germination of any grain - wheat, barley, oats or rye - the enzymes necessary for the conversion of starch into sugars are liberated, and then the growth begins. If this continues, starches are used up, so it is important to stop the growth as soon as the shoot and root appear amongst most of the grains. This is usually when the acrospire (rootlet and shoot) are one third the length of the grain.

Often, descriptions in the archaeological and anthropological scholarly literature of how to make malt are not accurate. Some describe malt as 'toasted barley sprouts'. Anyone who says that malt is like toasted, sprouted barley, suggesting that it is something like dried bean sprouts, have obviously never handled proper malt.

It is very important to talk to a maltster to understand how to make malt, to ask the practitioners, the skilled people who make it. Craftsmanship not scholarship.

Graham brings a 25 kilo sack of crushed malt from the brewing suppliers into the house. Then he makes beer with it, using basic equipment - a mash tun, a boiler and fermenters. Lots of people have tried Graham's home brewed beer and it is considered to be top quality, good and tasty.

What is this crushed malt in the sack?

Where does it come from, who makes it and how?

As I was doing the mashing experiments in the garden, using beeswax sealed earthenware bowls as mini mash tuns, I became more and more interested in the malt and how it was made. I studied the science of grain germination physiology, learning about what happens inside the grain as it begins to grow. It is fascinating and complex, worthy of a blog post of its' own.

this post was co written by Graham and Merryn

No comments:

Post a Comment